Building a Broken Window: web security by counter-example pt.1

I recently decided to develop HeadPage a Django-based ‘Damn Vulnerable Web Application’, inspired by the eponimous DVWA and nVisium’s django.nV. In this series of posts I will discuss/explain the main vulnerabilities present in HeadPage, as well as some of concepts and ideas in securing webapplications, hopefuly in a well-humored and equaly well-informed fashion.

Why make a broken site? Why write this blog?

First and formost I wanted to learn more about Web Applications and cybersecurity as a whole, and so, while experimenting django.nV and some others, but they were either too focused/small scale or were far too complex in a way that would require some good amount of time studying the codebase to reach a deeper understanding of the vulnerabilities therein. Wanting some middle-ground between a relatively small codebase and a realistic(ish) looking web app (and some concrete examples of SQL Injection, Remote Code Execution, Open Redirect and Unrestricted file upload), HeadPage came to be.

As for this blog and blogposts, It is in part to humble(?)brag to other folks “Look, I have a blog where I post about security, I’m basically an unsung Troy Hunt or Pierlugi Paganini, I mean business”, and in part to force me to summarize what I learned and hopefully have it be useful for someone else.

Let us begin.

User Data and Registration

Like in many other sites, users can sign-up for an account in HeadPage, you know the drill: unique username, good password, memorize it well, etc. And it is in this step that the security screw-ups begin.

When create an account, your user information is sent through an HTTP POST request to the server running the application, which then saves said data in a database that is hopefuly secure, with proper access controls and encrypted (For the sake of brevity, we won’t discuss the specifics of database security ). And of the user’s data, arguably the most important, and that requires special care is the user’s password

Hashes and Secure Password Storage

Unless you are planning to land a job on Facebook you should not store the raw, plaintext password for in the case of a data breach, the users’ passwords and their accounts on other sites, which a large percentage use the same password are vulnerable to attack. The solution is to store a salted hash of the original password.

Pictured - a salted Hash

Picture by AaronY

Jokes aside, it’s a very convinent analogy (and, after all, that’s where the name hash comes from).

A Hash function is a one-way function that takes an arbitrarily-sized input - in this case the password - and return a fixed-length identifier that is unique to that specific input, and by one-way it means that given the identifier, one cannot (or should not be able to) calculate the original input, and that any change in the input will (or should) result in a completely different output.

The problem with only hashing the passwords is that, should an attacker get his hands on them, he can start calculating new hashes en-masse (or consulting pre-hashed lists), by either bruteforcing all possible string combinations or from wordlists until a match is found. While long and complex password can definetly make the “cracking” of hashes more costly, computationally speaking it’s only a matter of time until a solution is found.

Enter the Salt, a randomly generated string that is appended or prepended to the password before calculating the hash. By making the salt long enough (e.g. about the size of the hash), unique per user and also changing it everytime the user changes password, we can successfuly mitigate brute-force and dictionary attacks by removing the predictability of the hash. This way, for example, two users using the same password have completely different password hashes.

Not all hash functions are made equal however, the algorithm we use of the password hashing must be robust enough that finding the original message from the hash is unfeasable/impossible and that statistically possible scenario where two distinct inputs have the same hash output - an event called Hash Collision which could allow an attacker to access an account by entering the wrong passowrd - is sufficiently unlikely. For this, we must use modern, standard, reliable and battle-hardened, cryptographic hash functions - such as PBKDF2, bcrypt, Argon, etc.

There is much more to be said on the topic of hashing, if you are interested consider reading the following page on crackstation where the folks of Defuse Security go into greater detail: https://crackstation.net/hashing-security.htm

Django Implementation

Straight out of the box, Django provides the developer with all the necessary parts for user storage through it’s django.contrib.auth framework (which will be further discussed in the next section of this blogpost) and User Model. A “Model” is Django’s data abstraction layer called, a Python class to manage the types of data that are to be stored in the database, and behaviors for them. Not only that but the framework is also capable of handling user-specific permissions, authentication (as the name sugest) and other neat features.

from django.contrib.auth.models import User

user = User.objects.create_user('fulano','de tal','fdt@email.com','aNicePassword')

user.save()

As you can see in the example above, creating a user is trivial, but under the hood, and by default, Django is using salted PBKDF2 for password hashing, all without requiring extra effort by the web app developer.

HeadPage Implementation

It would be fair to summarize the desing philosophy of HeadPage as “contrarian by design”, so instead of using the built-in models, new models were created for Users and the files they can upload and new methods. In retrospect this decision slowed down development as many ready-to-use methods and benefits of the standard auth system couldn’t be used, but it did make the backend more hack-ish.

In HeadPage, the user’s password has it’s length to 16 characters, with no minimum password policy implemented, furthermore they are hashed with SHA1 - an older algorithm that is now considered unsafe - and no salt is added. In addition to that, as stated above, the database is a plain SQLite with no encryption or additional security controls implemented.

With a preliminary analysis, HeadPage already suffers from three of MITRE’s Common Weakneses as defined in their CWE database

CWE-327 Use of a Broken or Risky Cryptographic Algorithm

CWE-759 Use of a One-Way Hash without a Salt

CWE-311 Missing Encryption of Sensitvie Data

Authentication

Very well, we registered a user, but how do we authenticate our users into our site? How exactly does “log-in” for web applications work?

Let us recap some basics of The Hyper Text Transfer Protocol, the backbone of the world wide web. HTTP is a stateless protocol, that is to say that a server (usually) does not store any information regarding it’s clients and their requests. This way each request is treated individually, it’s origin is not considered in it’s processing.

But in the case of an authentication system we need to identify who sent a request, and to store state of the communication. To achieve this, the server asks for the client to store cookies, a piece of data that the browser will send in all future HTTP requests to that site, thus identifying itself to the server.

Django Implementation

In Django this transmission of cookies and server-side storage is abstracted by the concept of Sessions that integrate seamlessly with the methods for authentication.

A code snippet from the Django docs show just how easy the whole process is.

from django.contrib.auth import authenticate, login

def my_view(request):

username = request.POST['username']

password = request.POST['password']

user = authenticate(request, username=username, password=password)

if user is not None:

login(request, user)

# Redirect to a success page.

...

else:

# Return an 'invalid login' error message.

...

authenticate() returns us the user model instance (if the password and username are correct), and after running login(), cookies containing a sessionID are sent to be stored by the browser, and the User instance of that user can easily be accessed by means of a .user variable in the HTTP request objects.

For futher reading: https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/3.0/topics/auth/default/#authentication-in-web-requests

HeadPage Implementation

So here’s how HeadPage jurry-rigs the session/authentication backend - First, we’ll create a substitute to the default authenticate function that will recieve a username and password and return the instance of the User Model.

def get_password_hash(password):

return hashlib.sha1(password.encode()).hexdigest()

def authenticate_user(username,password):

"""

This is a warped clone of an 'authenticate' as defined in the django docs

"""

password=get_password_hash(password)

try:

q = list(User.objects.raw("SELECT * FROM social_user WHERE username='{}' AND password='{}' LIMIT 1".format(username,password)))

return q[0]

#Generic exception = bad practice!

except Exception as e:

print(e)

return None

A keen eye will notice that the code above is not only ugly, but also that there’s a very critical vulnerability there (that will be discussed in the second part of this series)

We’ll still use the Sessions to keep track of the original user of a given request. As we are not using the default User model, won’t have access to the .user variable, however we can emulate that behaviour by manually adding a new variable to the Session, user_id which will store the primary identifier for that user account. This way the user object can still retrieve with relative ease in other functions.

Below is a snippet of the login code for HeadPage that implements the idea.

if form.is_valid():

user = authenticate_user(form.cleaned_data["username"],form.cleaned_data["password"])

if user != None:

request.session['user_id'] = user.id

return redirect(url_to_redirect)

To summarize, it is a very hackish, and not at all efficient way of handling the users session.

Encrypted Connection

If the exchange of information between the user and the application is susceptible to eavesdropping and interception in general, all security mechanisms discussed thus far will be, in all practicality, little more than window dressing. All communications should be properly secured using TLS/SSL, which enhances TCP connections with encryption, integrity and authentication.

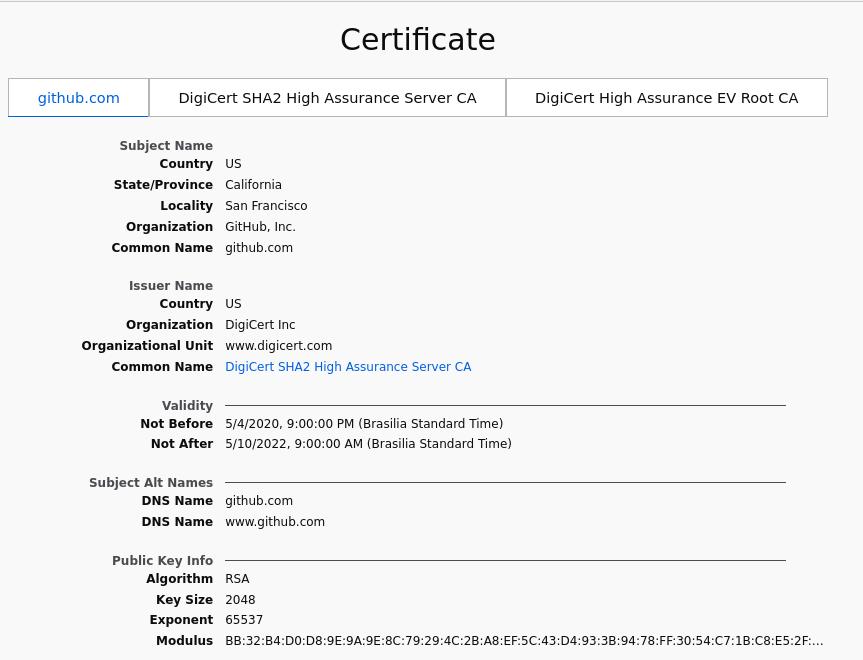

The broad strokes of the workings of TLS/SSL are as follows:

- After establishing a TCP connection with the server, a client starts a SSL handshake

- The server responds with its Certificate - a file created and signed by a well trusted third party called a Certificate Authority (CA) - that proves the server is who it claims it is, and includes the server’s public key.

- Using the public key, the client sends to the server a Master Secret. This secret will be used to generate new keys (known as session keys), which will encrypt, validate and authenticate all other data transfered between them for the duration of the session.

Kurose and Ross’ Computer Networking Chapter 8.5 was the basis for this simplified explanation and is a recommended read. The chapter’s slides are available here

By encrypting all the data sent to the server, we can securely submit our password to be hashed in the backend. Originally I believed that it would be more secure to just hash the password in the front-end, in the browser, but as pointed out once again by Defuse Security, the hash would become our password, as the server would recieve it and check against it the database. But remember, the point of hashing in the first place is precisely so that if the hash database is compromised, an attacker would not be able to authenticate as the user. We can still use client-side hashing however, but if we do so we must take into account the client-side salt, compatibility and hash in the banckend as well.

HeadPage does not use TLS/SSL, awarding it yet another CWE:

CWE-319 Cleartext Transmission of Sensitive Information

Coming up

In the next post, we will dive head-in HeadPage’s juicy vulnerabilities: SQL Injections, Remote Code Executions, and more!

Stay tuned, and thank you very much for reading.